Introduction

On this page, the entirety of a proof’s lifetime in the Boundless Market is covered; starting from a proof request to bid submission and lock in by a prover, through to proof submission and finally to proof verification. This overview is aimed at app developers i.e., requestors, and therefore for simplicity, it will abstract some complexity away from the specifics of provers. This will be covered in its entirety at a later stage.

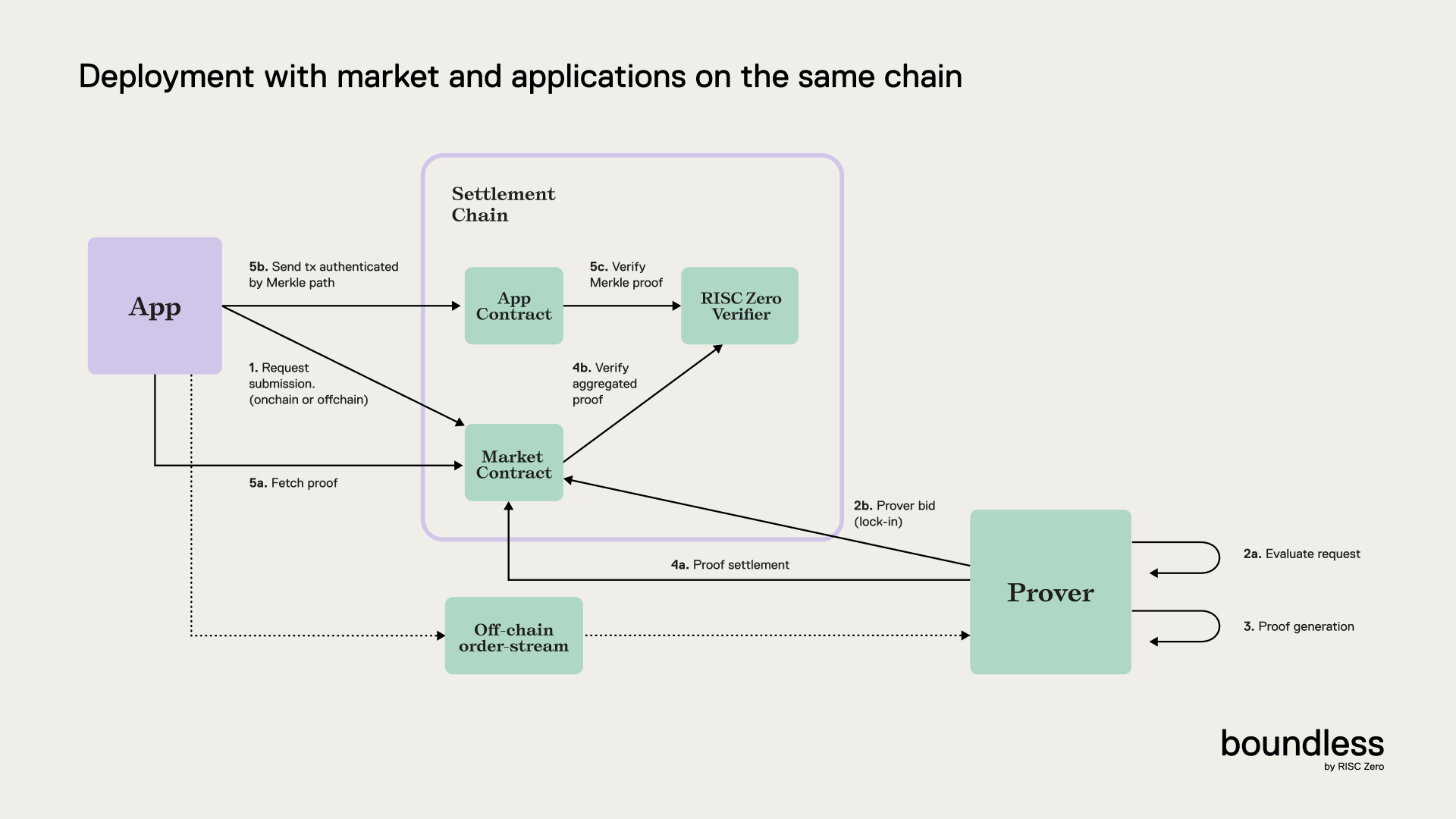

Figure 1: A process diagram following the lifecycle of a proof chronologically in the Boundless Market.

Overview of Proof Lifecycle

- Program development: Create a program with the RISC Zero zkVM.

- Request Submission: Submit a request with your program, input and offer.

- Prover Bidding: Provers evaluate and bid on the request.

- Proof Generation: Prover generates the proof.

- Proof Settlement: Market verifies the proof, ensuring it fulfills the request, and releases funds upon success.

- Proof Utilization: Application retrieves and uses the proof in their application.

Detailed View of Proof Lifecycle

1. The App Developer Writes a Program for the zkVM

For more info, see Build A Program, and Getting Started with the zkVM.

2. The App Developer (Requestor) Broadcasts a Proof Request to the Boundless Market

The app developer will start the proving process by requesting a proof from the Boundless Market. Requests can be sent onchain, in a transaction to the market contract, or offchain through the order-stream server depending on the user’s censorship-resistance requirements. When submitting a request offchain, they should first deposit funds to the market to cover the maximum price in their offer. The bid matching mechanism used by the market is a reverse Dutch auction. An application submits a proof request that contains parameters specifying the program to be proven, the input, and an offer.Offer Details

An offer contains the following:| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Minimum price | The lowest price the requestor is willing to pay. |

| Maximum price | The highest price the requestor is willing to pay. |

| Ramp-up start | Defined as a timestamp. |

| Length of ramp-up period | Measured in seconds since the start of the bid. |

| Lock timeout | Measured in seconds since the start of the bid. |

| Timeout | Measured in seconds since the start of the bid. |

| Lock collateral | The slashable amount if a prover fails to deliver a proof. |

| Parameter | Example Value |

|---|---|

| Minimum price | 0.001 Ether |

| Maximum price | 0.002 Ether |

| Ramp-up start | Now |

| Length of ramp-up period | 300 seconds |

| Timeout | 3600 seconds |

| Lock Timeout | 2700 seconds |

| Lock collateral | 5 ZKC |

BoundlessMarket.sol - submitRequest

The BoundlessMarket contract has a submitRequest function:

ProofRequest struct:

3. Provers Bid on the Request

After a proof request is broadcast, a reverse Dutch auction runs according to the parameters specified by the offer. From the moment the request is broadcast, the auction price is the set at the minimum price specified in the offer. During the ramp-up period, the price is increased linearly up to the maximum price. After the ramp-up period, the price stays at the max price until the request expires. At any time, a prover can submit a bid, accepting the current price and winning the auction. Because the price only increases, the first bid is the best price for the requestor. When the prover submits their bid, the auction ends and they “lock” the request. Once a request is locked, only that prover can be paid for submitting a proof. This ensures that the prover will not waste their compute resources, as they know no other prover can take the request instead. By increasing market efficiency, this lowers prices. However, locking a request requires the prover to put up collateral, which will be slashed if they fail to deliver a proof before the request timeout. Slashed collateral is used to incentivize other provers to fulfill the request in the case where the locker fails to deliver the proof. Requestors choose the collateral value according to their application’s requirements. A low collateral value may result in a better price, however there would be less incentive for another prover to fulfill the request in the case where the locker fails to deliver the proof. A higher collateral value may decrease the chance an unreliable prover will lock the request. An unlocked request can be directly fulfilled, without first being locked. When this happens, the prover will be paid according to the auction price at that moment. Applications may disable locking entirely by setting the collateral amount impossibly high (e.g., higher than the total supply of the collateral token), ensuring that no prover can lock the request and disincentivizing others from proving. Provers will calculate the minimum price at which they are willing to prove a request based on a number of factors. These can include:- Cycle-count of the program execution, determining the proving cost.

- Lock-in collateral required

- Timeout and LockTimeout length, determining how long they have to complete the proof.

- Input and program size, determining bandwidth costs to download the request.

4. The Prover Submits an Aggregated Proof, and Upon Successful Verification, the Reward Is Released to the Prover

To be paid the request reward, and for their lock-in collateral to be returned, the prover must submit the proof prior to the offer’s expiration.Provers Batch Proof Requests

The proof submitted by the prover is an aggregated proof, which proves a batch of program executions. Why is Boundless designed like this? The direct goal of aggregation is to amortize the cost of expensive proof verification onchain, both for the requestor and the prover. Let’s start with an assumption: the prover has locked themselves into a number of individual proof requests. A naive implementation would be to have the prover generate a proof for each proof request, send each proof onchain and pay gas for each verification. This would work, but it would cause a lot of needless expense; the prover has to send each individual proof onchain to the market contract. This will rack up expensive gas costs, affecting the efficiency of the market. Starting with the provers, a clear solution is to batch the proof requests together. Instead of proving one request, sending that proof onchain, and moving onto the next request, the prover can work on multiple proof requests and prove each one without interruption, submitting one aggregated proof for the whole batch.Prover Submits the Requested Proof On-Chain

In order to fulfill a batch of requests, and receive payment, the prover provides an aggregated proof. This aggregated proof is constructed as a Merkle tree, where the leaves are the proofs for the individual requests in the batch. At the root is a single Groth16 proof that attests to the validity of all proofs in the batch. Each individual request has a Merkle inclusion proof linking it to the root. Once the root is verified, the result is cached and the Merkle inclusion proofs are cheap to verify onchain. When the prover submits the aggregated proof, the Market contract verifies it and pays the prover if all conditions are met. At the same time, the contract emits an event that signals to the requestor that their request is fulfilled, and provides the Merkle inclusion proof.The requestor can use this Merkle inclusion proof as an effective representation of a verified execution, and use it as such in their application.